A look at the Dan River.

TURBEVILLE – Two of the greatest moments in The American Revolutionary War were not, in fact, battles. They were actually river crossings.

Most school-age children know about the famous Crossing of the Delaware River on Christmas night 1776, which allowed General George Washington to surprise Hessian forces in Trenton, NJ and gain a much-needed victory for the beleaguered Continental Army.

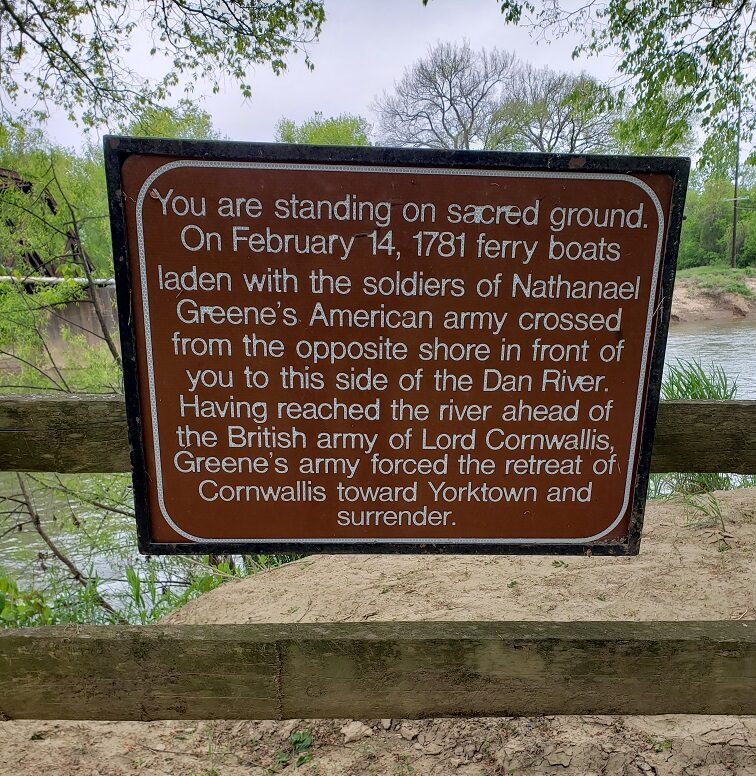

The second river crossing was the not-so-famous Crossing of the Dan River on Feb. 14, 1781, which took place in modern-day Turbeville and Boyd’s Ferry in South Boston. Unlike the Crossing of the Delaware, this lesser-known river crossing did not lead to a victorious battle, but was part of a tactical retreat that helped swing momentum to the Continental Army, and end the war later that year.

‘A Source of Immense Pride’

Jennifer Bryant, director of the South Boston and Halifax Museum, affirms The Crossing of the Dan, “is a source of immense pride for this town.” Jennifer was in charge of moving the Crossing of the Dan exhibit from its former home at the Prizery to a front-and-center spot at the South Boston and Halifax Museum to celebrate its 240th anniversary. Bryant said that bringing the exhibit from the Prizery to the museum, at 1540 Wilborn Ave., has made it “more accessible for a younger generation.”

Bryant and the museum staff added resources to the exhibit and relaunched The Crossing of the Dan with much pomp to commemorate the anniversary.

Bryant said, “The Crossing of the Dan is not a major battle and is often overlooked. However, had it not occurred, we might not have had Yorktown,” the triumphant final siege in the War for Independence.

The Crossing of the Dan, Explained

It was late in 1780, five years after the Battle of Lexington and Concord, when newly appointed General Nathanial Greene arrived in Charlotte, N.C. to find the Continental Army in tatters. Greene realized he could not afford a head-on conflict with the better-supplied and superior-numbered enemy. British General Cornwallis was from an era of old European battles in which soldiers fought on an open field.

Men formed lines like pieces on a chess board. They fired, reloaded their muskets, and continued until one side won. Greene knew that if this European battle tactic were employed, the Continental Army would be decimated. Instead, he employed hit-and-run tactical conflicts. Greene also split his army into two forces to draw the British away from their supplies and wear them down.

Greene placed half of the forces under the command of Daniel Morgan, who had just come from a massive victory at Cowpens, S.C. Morgan’s tactics at the Cowpens battle are studied in military academies to this day. General Cornwallis was so enraged at the Cowpens defeat that he, like Melville’s Captain Ahab, became single-minded in his pursuit of Morgan’s troops, who had captured hundreds of British soldiers as well as weapons and resources.

Driving The British to Destroy

Cornwallis even destroyed some of his own burdensome wagons and supplies to speed up his army in pursuit of his “white whale.” There were a few skirmishes between Greene and Cornwallis on the race to the Dan, but Greene knew better than to turn and fight the overpowering enemy for any extended period of time.

Greene and Morgan sprinted north with the British close behind. The strategy was to avoid a prolonged battle and draw the British farther away from their supply lines. This would weaken the enemy physically, mentally and morally and help even the odds when the time came for a head-on battle. A little over a half century later, this same draw-out-and-drain tactic was used by General Sam Houston when he defeated the nearly double-in-size army of Santa Anna in just 18 minutes at the battle of San Jacinto, after the Alamo.

Running Towards The Dan

General Greene sprinted towards the Dan River and split his army a second time. He sent a decoy group towards the location of modern-day Danville to distract Cornwallis and give the Continental Army the time needed to cross the Dan with artillery, wagons, and gear. They crossed the Dan River on Valentine’s Day in 1781. Minutes later, British troops arrived on the south side of the river, but with no ferry at their disposal, they were unable to follow.

This river crossing allowed the Continental Army a week-long reprieve to rest and resupply, and was one of the final pivots in the War for Independence. As Cornwallis moved back south, his troops were ambushed by the Americans, which further demoralized them. In the next battle — at Guilford Courthouse — Cornwallis lost 532 men.

By the time they met on the final battlefield in Yorktown, Va., on Sept. 28 of that year, Cornwallis had lost nearly half his army in pursuit of General Greene. Between the French army and navy, and Continental troops, the victory was complete on Oct. 17, 1781 with negotiations lasting two days. General Cornwallis, in his pride and obsession over winning the south, lost the war. Cornwallis was so distressed at the defeat at Yorktown that he sent Brigadier General Charles O’Hara to the surrender ceremony in his stead.

Crossing of the Dan Overshadowed

As the decades turned into centuries, other names and events overshadowed the Dan River Crossing, and the event rarely made it into school history books. However, that muddy river acted like a moat of protection for the Continental Army. Had the Dan River not been in that strategic spot, we might still be under British rule to this day.

The next time you drive towards Riverdale, remove, if you will, the stores and paved streets from your mind. Glance over at the old Boyd’s Rail Bridge as it sits over the Dan. Imagine, for a moment, what it must have been like nearly two-and-a-half centuries ago for our ancestors who stood in that very spot where the bridge pylons reach down into the muddy river bank.

Men once rushed through the woods, loading cannons onto wooden ferries to sprint across this fast-flowing, frigid, swollen river. Both the sight and sound of the enemy were upon them, and the only way to survive was to wait their turn for the ferry. To them, that river represented survival — and escape — for the entire southern Continental Army. Escape, which ultimately led to victory.

Q: Where can I find this museum?

A: 1540 Wilborn Ave, South Boston

You can also reach museum officials at (434)-572-9200 or at www.sbhcmuseum.org

John Theo Jr. is relatively new to South Boston but not new to writing. He has authored several books and penned many articles. Hyco Lake Magazine is thankful to share his perspective on our community. Please welcome John and get to know him better by going to JohnTheo.com.